The commissioned portrait is an opportunity Sharon Sprung embraces. All portraits, she says, not only convey the subject’s likeness but “tell us (the viewers) who we are.” – BY MAUREEN BLOOMFIELD

This article one of many available to members in the eBook “An Artist’s Guide to Portraits.”

At any art museum, the biggest crowds are always around pictures of people—at the Louvre, around Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, at the Rijksmuseum, around Rembrandt’s self-portraits and, at the Met, around Sargent’s pictures of friends. In today’s art market, however, pictures of people rarely appear in gallery shows or at auction Sharon Sprung has taken note of this contradiction. “I wish I could convince people of the importance of portraiture,” she says. “Portraits are indicative of who we are; they tell us our history.”

Sprung was fortunate to have studied with two masters of the genre, Harvey Dinnerstein and Daniel E. Greene. Beyond or apart from technique, however, is the impetus behind portraiture, which she explains this way: “I love taking the subway. I want to be with people. I’m not at all conscious of what I’m doing, but I can tell (apprehend, understand) each person right away.”

Growing up in Brooklyn, Sprung was a quiet child; after the death of her father, when she was 6, she stopped speaking altogether for a year. “I was trying to figure out the world without words,” she says. Even now, she tells me images are more eloquent than words. She loves being with people because she loves to watch them. “The best analogy is that I am a person in a foreign country, without language, watching.”

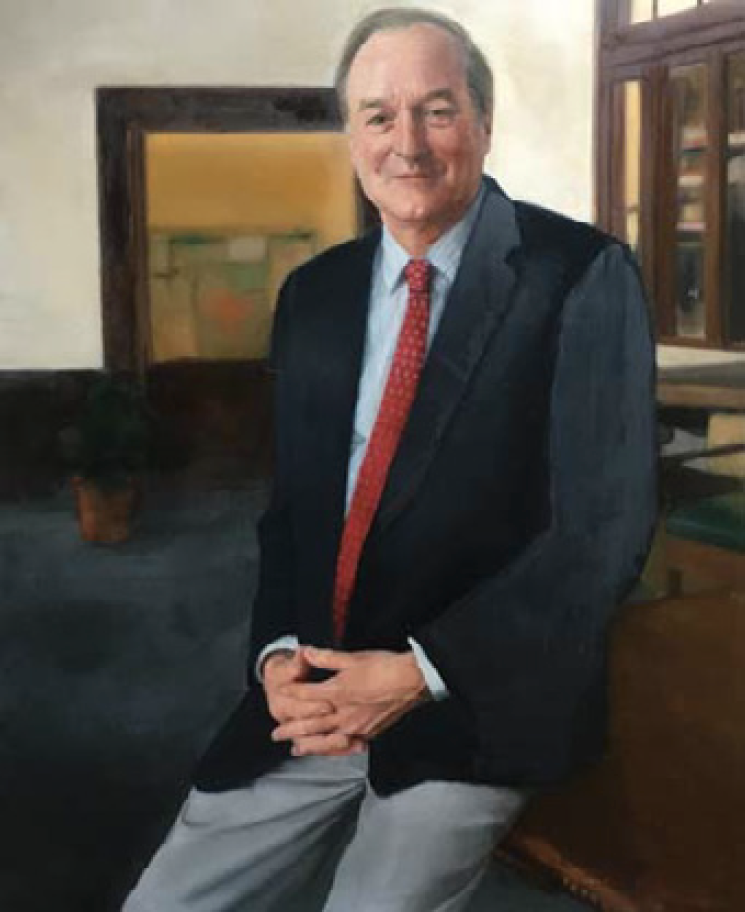

PAINTING A COMMISSIONED PORTRAIT

“Commissions, by their nature, are a collective creation, so I always discuss the way the clients see the process and what they want from the outcome,” says Sprung. The subject is David Harmon, the headmaster of Poly Prep Country Day School, an independent school in Brooklyn. Sprung spent two days there, attending assemblies and walking the halls, “getting a sense of the headmaster’s commitment to students.” The question: Where to put him? She considered about 15 settings, took photos and made sketches in a process that took several weeks. When she showed the sketches, it became, says Sprung, “a communal process since everyone turned toward the same pose. The setting we ended up with was the center of the school, the entranceway where everyone passes through: a nice comment on his legacy.”

OVERTURNING ASSUMPTIONS

Now acclaimed as a painter and beloved as a teacher, she bypasses the conventional wisdom that says that pictures of children are problematic, because they can be seen as precious, and an attendant assumption that asserts that a commissioned portrait is somehow lesser, because it’s identifiable as one. Both assumptions follow from the inevitable compromises that arise when an artist is paid to please, whether it’s a leader in industry or a parent.

The history of art tells a more nuanced story, however. Princely donors kneeling at the side of a medieval altarpiece; 18th century kings and cardinals portrayed on thrones; 19th- and 20th century power couples surrounded by their collections — portraits document their times, and artists have always depended for their livelihood on patrons, whether in board rooms or at court.

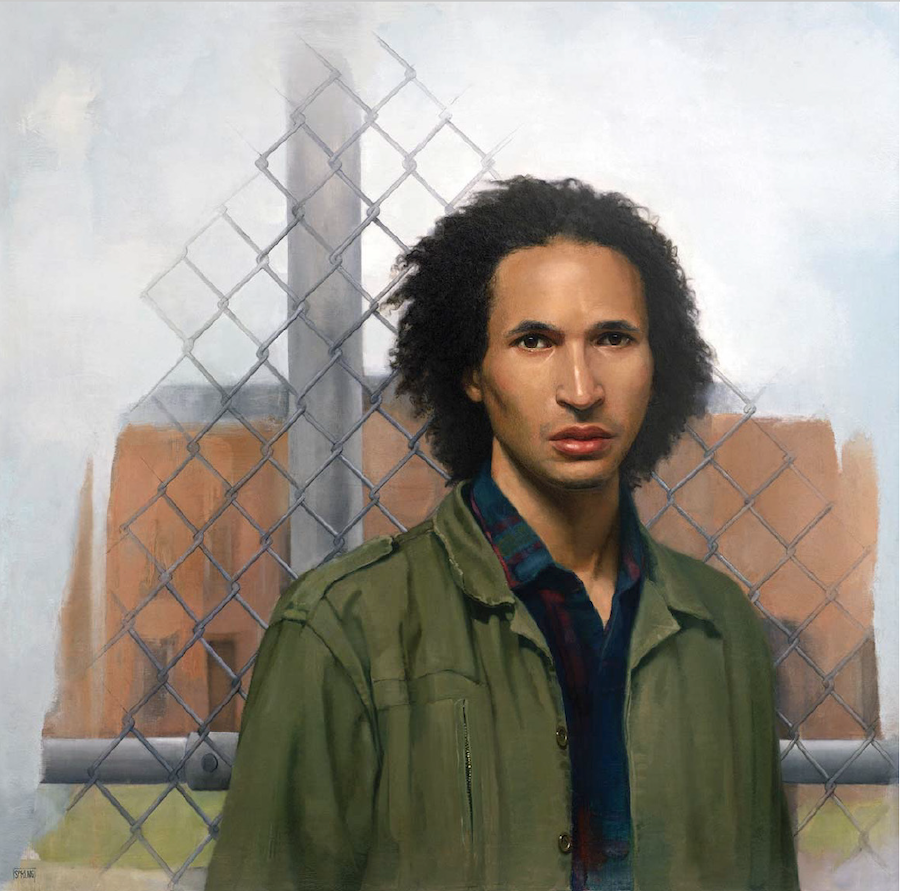

Having accepted a commission to paint a child’s portrait, Sprung sets up a play date; for a commission of an adult’s Portrait, she “follows” the subject—taking photographs of where he works and watching how he interacts with colleagues and underlings. For a judge, she’ll observe her in the courtroom; for a dean, she’ll be a fly on the wall in the halls of the school (see Painting a Commissioned Portrait).

Some of her most beautiful portraits, like Screenwriter’s Daughter are of young women she has known their entire lives, because, as children, they were friends with her son. Indeed, one of the mysteries of portraiture is that a good portrait records not just a likeness but a life; for that reason, the past is prologue. In the event she has accepted a commission to paint someone new, Sprung says, “I always ask to see photographs taken when the subject was a child.”

LOOKING TO SEE

In the classes she teaches at the Art Students League, Sprung advises her students to spend time studying the model: “Look harder; look more than you paint,” she says. She places the palette between where she’s standing and the panel, which prevents her from working too close to the surface of the painting. Restless by nature, she tells students, “Remain at a good distance from the work and keep moving.”

After posing the model, she positions herself parallel to the picture plane and starts with a gesture drawing with rough lines made with Payne’s gray mixed with turpentine. “Movement and composition are the most important considerations,” she says. “I strive for fluidity, working all over the canvas, trying to get the life and the essence of the pose.”

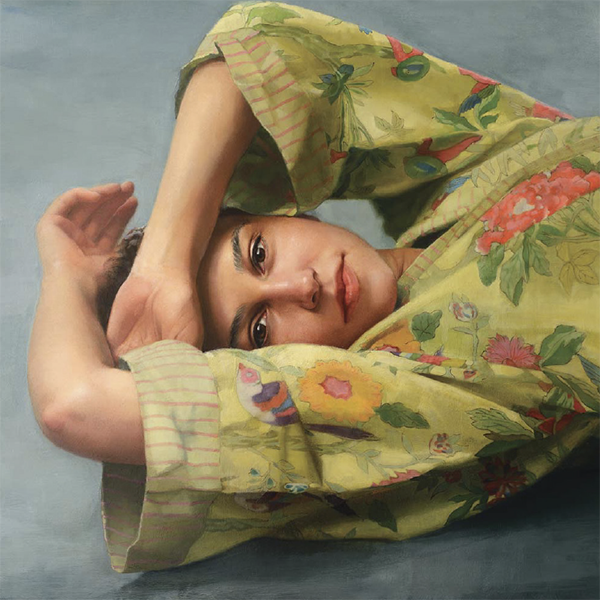

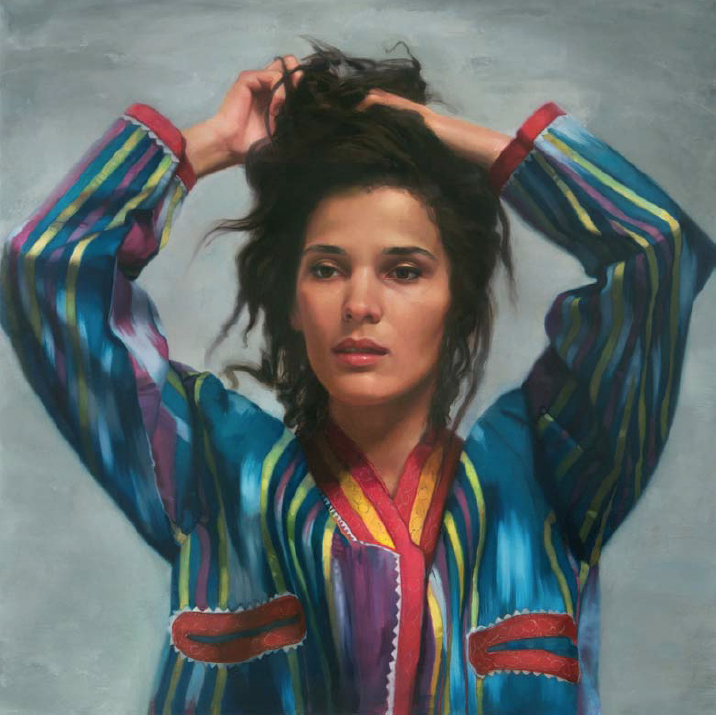

“Gesture is emotion in movement,” she says. “Drawing the model and the space around her at the same time is essential to balance the dynamic exchange between the positive and negative spaces.” Many great portraits are studies in light and shadow, but not Sprung’s. She uses color, at first, to help her find the figure’s contours—blocking in bright color behind the gestural drawing and then working, against the color, to distinguish between the color field and the figure. In this, she resembles David Hockney.

A SQUARE AS AN EQUILIBRIUM

Along with color, the square format distinguishes Sprung’s work from portrait painters in the past and now. “The square format suggests to me,” she says, “equanimity; it creates a place of calm so that the viewer wants to stay with the painting. I find the square especially good for children.” The square, whose sides are equal, suggests stasis in contrast to the movement implied by the spiral and the eternity implied by the circle. The four sides of the square can suggest the four directions (east, west, north, south), the four elements (earth, air, fire, water), and the four seasons (spring, summer, fall, winter). The grandeur of the conventional portrait of a king or queen (by Ingres, Velazquez, Rubens, etc.) attests to the power of the subject, often enthroned, on horseback, or indomitable in the midst of a whirling storm. The elongated, vertical rectangular format stresses the metaphorical height of the personage and aligns him with sky. In contrast is the humble square, with four right angles that assert stability and innocence (as in a child’s drawing of a house), particularly resonant for a portrait of a child, who is inchoate, not having reached the age of reason and not having had a chance to decide who or what she is.

ON COMMONALITY

It is hard for me to express the importance that I place on portraits. To me, they are visual biographies, proof the person depicted lived and breathed and created who they were. I have only a few photographs of my father; I held and hold tightly to the few visual memories of him that I have. With my portraiture, I want to be a witness, to explain—beyond words—who my subjects are.

This was especially true for the several posthumous portraits I have done, perhaps most notably of the first woman congressperson, Jeannette Rankin.

For me, painting people in my own figure work or commissioned portraits is the meaning of my life. I am a visual person—it is my orientation to the world. The visual gives a sense and order to the chaos. – Sharon Sprung

MATERIALS

Oils: Vasari flake white, yellow ochre, raw sienna, permanent red, scarlet sienna, alizarin, raw umber, Payne’s gray, cobalt blue

Tools: palette knives from small to large

COLOR AS FIELD

In the standard Dutch, later Baroque, neo-classical, and romantic portrait, the figure usually emerges from shadow, as if to imply that the subject illumines the darkness. Sprung’s portraits, in contrast, just as dramatic, are always bright. “I love color,” she says. “It’s a major impetus in my work. Paintings are decorative, initially—they call the viewer to a design of color and light.”

Beauty and even severity don’t have to be dour, in other words. The first principle is pleasure. “To me,” Sprung says, “the first motivation is to hold the viewer—so that she stays in order to study and to feel. I have to create for her the motivation to investigate the larger meaning of the painting.”

The colors she places behind and around the figure are bold and clear, a field of pure chroma, with few, if any, gestural flourishes. “I use strong colors,” she says. “For me it’s like an arrangement in music. I choose notes that complement, enhance and contrast with each other. Color to me is the first element in a painting; in a way, it’s the starting point.”

Sprung’s house is filled with color, with fabrics, carpets and textiles, even “hanging from the banisters.” “Contemporary design,” she says, “seems so often devoid of color, lacking the subtlety and warmth that well-orchestrated color provides.”

A PORTRAIT IS A PORTRAIT

When I complimented Sprung on her portraits of children, portraits that assert the subject without sentimentality, she was quick to say, “It doesn’t make a difference to me how old or young people are. I don’t think of myself as a painter of children. I don’t see the distinction.”

To a similar end and inspiring a similar response, I asked her to think about the differences between a portrait commission and “her own paintings.” She told me something else I didn’t expect: that there’s not that much of a difference. “The process is similar,” she says. “When I conceive of my own work, it’s an idea or a feeling or an emotion I want to pursue, investigate and struggle with. I am always hoping that in the specific I will find or embrace the universal that investigation never stops.”

WORKING ABSTRACTLY FIRST

In the past Sprung has described her process and work as a way of uniting figuration with abstraction. Her figures are beautifully (almost classically) rendered, but rather than place the figure in Renaissance depth and space, Sprung poses the figure against a field of color, a decision that pays indirect homage to late Abstract Expressionism and Color Field pictures of the ’50s and ’60s.

Watching her do a demonstration for a class is a thrill, as it seems that she finds rather than imposes an outline or a contour or any mark that indicates where the figure begins and the ground ends. Working quickly with black marks and palette knives laden with color, she goes over strokes, correcting them, revising them, erasing and re-emphasizing, while always staring at the model, until, seemingly all of a sudden, the figure comes to life. “All my paintings start abstractly,” she says, “That means that I need to trust myself and my skills in drawing and painting—to allow things to weave together slowly. It starts with broad shapes and colors, and decisions to refine and refine, or to leave other areas loose—so that the picture can breathe.” The palette knives she prefers to brushes give her “an opportunity to be more physical.” She explains, “The knife allows for a layering, an effect that feels more like flesh.”

A SONG OF PRAISE TO PORTRAITURE

The value of the formal portrait in a society is twofold. It documents an event in that it preserves the likeness of an actor in history. It also becomes a substitute for its subject and in that way can inspire devotion. Thus, it’s important for an institution to have portraits of its directors and also important for mourners to have a portrait of a beloved parent or child. “I feel, when I do a portrait, as if it’s an expression of love,” Sprung says. “I know it’s finished when I walk into the studio in the morning and it’s separate and breathing.”

A humanist, Sprung argues that portraiture “connects us to and communicates our humanity.” Indeed, there is a lovely universality in the fact that pictures of a child at the start of his life, of a head of state in his prime, or of an artist near death can all make us cry. “Portraits confirm the importance of all of us, singularly and collectively,” she says. “They reflect our common experiences; they elevate and comfort us. We have walked here before, we have felt this before without words. We all understand the subtle differences in the cast of an eye, the turn of head, the expression of a mouth. Portraiture tells us we are here; we are respected or loved or that we have earned a place in the larger venue of history.”

It goes without saying that the artist would have loved a portrait of her father, who died over 50 years ago. “He was a strong presence and I feel I have an obligation to give his life meaning. I am the only Sprung,” she says. “Every time I sign a painting, it’s with his name.”

Maureen Bloomfield is a former editor of The Artist’s Magazine.

Meet Sharon Sprung

“I feel fortunate in that most of my now long career has been spent creating my own work and exhibiting it,” says Sprung. “I’ve had many one-person and group shows at Gallery Henoch in New York City. For 35 years the gallery has encouraged and supported my growth as an artist.” Sprung attended Cornell but got her art education at the Art Students League, where she now teaches. She has garnered many awards from the Portrait Society of America, International Artist Magazine and The Artist’s Magazine, for which she has served as a juror for the Annual Art Competition. “I consider my commissioned not separate,” she says, “but part of my artistic path.” Visit Sprung’s website at sharonsprung.com.