Back to the Eighties – Pushing

Pixels

|

| Back to the Eighties – Pushing Pixels |

This time, we take a step back

in time to the 1980s, the decade that provides the subject matter of many of my

own artworks. It was also the decade where my life as a professional digital

artist began, one pixel at a time. In my latest discussion we take a deep-dive

into what it was really like creating digital art in the 1980s and why todays image

editing tools and modern equipment can never quite achieve truly authentic

retro recreations.

Being what some would call, a

dinosaur of the 8-bit era, I tend to get asked more and more of late what it

was like creating digital art in the early days of home computers and whether

or not it’s easier today with all this new-fangled technology. I’ve been

surprised at just how many people are now taking an interest in a decade that

many of them were born way after, but it’s easy to figure out why, for a new

generation it’s just like a previous generations fascination for the 1960s.

So to answer that question

about whether things have become any easier with all of this brand new

technology that can seemingly be made to do anything, in short, it is massively

easier to create anything today and do so with so much more precision but it’s

also massively more difficult to create digital art if you want to create a

specific or authentic vintage look. Sure, you can make a facsimile but that’s

not quite the same.

So this time we will be going

on a journey through time. We will take a look at the early home microcomputer

market and how it gradually began to influence how the production of art would

make the transition from canvas to screen. We’ll also take a look at just how

much digital art technology has changed since the early 1980s. It’s a deep dive

for sure, but one that merits the three months or so that this article has

taken me to write because those early moments in tech-history are worthy of

preservation.

We’ll also take a look at how

early digital art was created and why recreating authentic vintage style art

today for retro and vintage collectors is massively more complicated with

modern tools than it was back in the decade that also gave us Rick Astley and

Madonna. To top it all off, we’ll also be exploring the very reasons why so

many people are suddenly finding comfort in collecting pixelated memories from

their childhoods, a trend that continues to keep us original pixel artists busy.

|

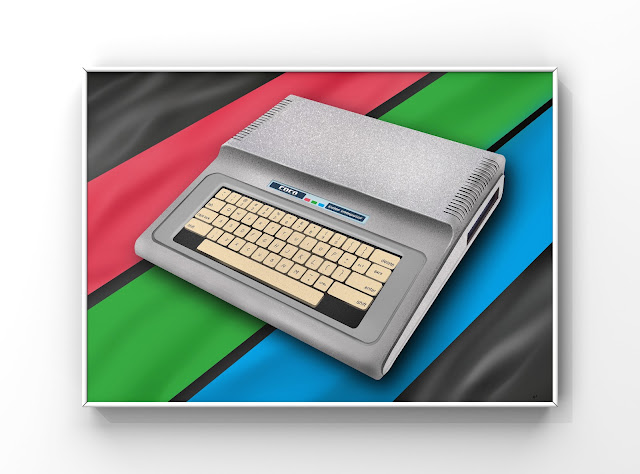

| Eighties Toy Keyboard by Mark Taylor – I think every kid had one of these, this one doesn’t make any noise! |

Everyone who knows me will

know how much I love the 80s. It was a decade that presented me with career opportunities

that would last a lifetime, or at least a lifetime up until now and I hope it

will continue for many years to come. The 80s was also the decade that handed

me a collecting/hoarding habit that makes my studio and office feel more like a

museum at times.

I collect everything from 1980s

video games to the ephemera that came alongside them, right the way through to

early editions of some of the most iconic early computer magazines and of

course, I collect the artwork from the period. Much of that artwork from the

80s was inspired by The Memphis Movement, a style which defined the eighties

and is still used today. The eighties gave us a lot of history that we don’t

always necessarily or immediately associate with the decade and its importance

in society, art and design and popular culture.

I probably need to be clear

here, I don’t view everything 80s through a rose-tinted lens. The modern age

has a couple of positives over the 80s, I was younger for a start. We did have

bleak times, plenty of them, and to an extent, we’re seeing some of the same

things happen again today that we witnessed happening back then.

In the 80s we had stock market

crashes, the threat of extinction from a Cold War, general strikes and workers

just like today, were mostly disgruntled with the rising cost of inflation. So

I think there’s more than a direct comparison you can make with many of the events

taking place today. The world might feel different than it did a couple of

years ago for those who weren’t around in the eighties, but for those of us who

were around, I think we’re once again in familiar territory. Maybe the 2020s is

the 80s part two? Life was hard in the 80s but hey, at least we had great

music.

|

| History Repeating by Mark Taylor – kids were oblivious to the political turmoil and stock market crashes of the 80s, but it could be bleak! |

The decade wasn’t all about

shell suits and pop music, technology was being rapidly miniaturised and we

would witness a technological revolution just as important as the industrial

revolution that took place between 1760 and 1840. The 1980s were pivotal in the

evolution of technology as the decade would go on to shape the technology we have

come to now rely on every day.

|

| Dialling for Dollars by Mark Taylor – Innovation and turmoil, oh, and answering machines were a thing… |

We have to understand the past

to recreate it…

I’m all about preservation. My

retro collecting habit is borne out of a personal need to preserve historic

moments that were mostly never documented at the time. The only experience we really

have of the decade today is the experience that was around at the time, and a

lot of that experience is fading away year after year.

This need to preserve the 80’s

and especially the technical revolution is partly what has driven me to focus

more and more on my 80’s inspired works recently, although they have been a

staple of my creative output since the late 1980s when I would create commissioned

characters and supporting artwork often for fans of computer games.

My landscapes and abstracts

continue but what many people probably never realise when they view the work

that most people know me for, is that whilst I’ve managed to scrape a living

creating abstracts and landscapes, my bread and butter has always been rooted

in my work in pixel art, retro-inspired collections and commissions from a

group of tech fans who have never lost their enthusiasm for the period since

the golden age of the eighties and the decades either side.

|

| Kinetic Fields by Mark Taylor – my landscape and abstract works continue. We didn’t have wind power in the 80s, at least not like this, but many of us had bicycles with lights powered by a dynamo! |

My retro artworks all depict a

period of time through the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s, and this pictorial

preservation and celebration of history and innovation is becoming more

important too. The internet has grown exponentially and it has paradoxically

become smaller at the same time. We would once browse the web and explore the

new frontiers of the digital age, we could explore historic moments through the

lens of all those people who had set up their first websites using sites like GeoCities

and we were asking Jeeves for advice.

Today we visit virtual shop

windows that have had their displays dressed specifically for each of us

through the use of tracking cookies and everything else that didn’t exist even

in the days of bulletin boards, ARPANET and a hundred free hours of AOL. Early

search engines searched through content rather than adverts, and the results

would often be returned in all of their neon glory.

Today, the first pages, let

alone the first page of any search engine has become an advert. It’s next to

impossible to find useful information because we are now only served what the

tech giants think we want to see and we’re now at that place where they only

think we want to see adverts.

Maybe this website is too

old-school to be cool, I never ask anyone to sign up for anything, I self-fund

the whole shebang, I don’t run adverts and I try to provide useful information

which is rapidly eroding from our searches and to an extent our first thoughts,

and when you do find anything that is, you know, actually relevant, it usually

exists only on the outer reaches of internet servers and no one has any time to

find it because we expect immediacy today. Hey, you know the cloud is just

someone else’s computer right?

The subject matter during the

three decades that much of my work represents is broad, I paint everything from

skateboards (because they were cool yet dangerous) to the earliest electronic

gadgets, and for anyone else who lived their formative years during this time

or even younger fans of that time period in general, many of us remember exactly

how we felt when we picked up say an electronic game for the very first time.

Hopefully my vintage-inspired art

triggers a memory or two for many who view it, but that’s not necessarily the only

point of it. I really wouldn’t want such an important period of our technological

history to be lost because someone couldn’t be bothered to document it!

For those of us of a certain

vintage, we remember the emotions we displayed and the feelings we had at the

time and we even remember the distinct smell of ozone from new electronics, a

smell I never come across today but one I wish I could find again and bottle.

|

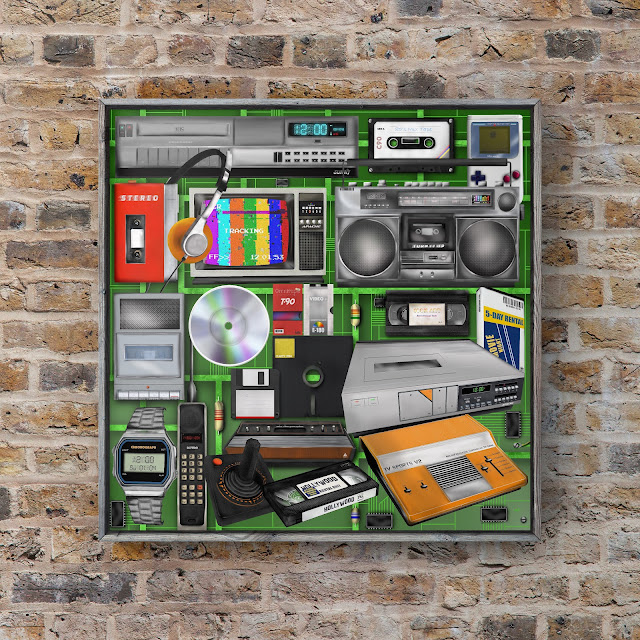

| Eighties Entertainment by Mark Taylor – every new device had a great smell of ozone. I think it was great, I remember it well, I think I liked it, maybe my memory is filling in the blanks? |

We remember how the device

felt, how heavy it was, and how it made us feel. It was magical because no one

had ever seen anything quite like it before and there has never been a time

since when the same feelings have ever been replicated with new technology in

quite the same way. Today, we have come to expect innovation and I think we

take it for granted a bit too much.

I even remember visiting a

store with my parents and seeing a home computer for the first time as if it

were only yesterday. The smell, the display, the excitement, the shelves and

shelves of games, and the ring bound manuals that would teach you how to write

simple code. Those memories were made at the same time I was in school so

subconsciously even that triggers further memories of friendships and times

when the responsibility monster wasn’t lurking around every corner.

The rabbit hole of nostalgia

runs deep in many of us, but this wonderfully complex paradoxical experience

doesn’t affect all of us, at least in the same way.

Nostalgia is a powerful form

of reminiscence that often takes the form of a first-person memory reminding us

of something, usually an event or experience when we were surrounded by friends

or family or we experienced moments of personal happiness. These moments can

become our anchors to happier times that can give us hope for the future.

Nostalgia wasn’t always seen

so positively though. More than 300-years ago it was commonly seen as a

disorder of the mind that had potentially damaging consequences. It was seen as

a form of depression where the person experiencing it would be unable to live

in the present. A Swiss medical student coined the term after observing the low

morale and spirits of mercenaries fighting overseas. The word itself originates

from Nostos, which is Greek for homecoming and algos, which translates to ache.

When we experience nostalgic

recall, not everything we remember is a perfect replica of the time, the

moment, the thing, or the event. Our minds do a very good job of adding mental

edits that make the memory more appealing which is why sometimes we feel

slightly disappointed when we find out that something from our childhood either

hasn’t aged too well or isn’t quite how we remembered it.

As time passed, the negative

connotations of nostalgia were replaced as numerous studies eventually linked nostalgia

with the human desire to reflect on happy memories of the past and some of

these studies have found that nostalgia is more akin to a coping mechanism,

often finding that this mechanism works

to counteract any feelings of depression. Rather than being a negative, today

nostalgia is seen as a positive.

Many modern studies describe

nostalgia as something that helps us to reflect on better times rather than

specific things, and many of these studies have identified nostalgia as being

something that can help lift our moods and reduce stress and it is able to

boost feelings of hope and optimism and provide us with memories that provide

hope that better times can be repeated again. I think that is exactly the reason why we are

seeing such a surge in popularity around collecting retro right now.

Some of these studies suggest

that it can even come to the fore as a defence mechanism but for many, nostalgia

I think, is mostly a force that provides us with an emotional experience that

can unify and unite. Certainly for me, collecting 80s memorabilia, culture and period

specific technologies, is as much about the surrounding community of

like-minded people who are collecting the 80s as well.

Being a collector of all

things 80s has not only put me in touch with many people from all walks of life

who are doing the same, it has taught me more than I ever learned in art school

about how and why art produces such strong emotions in people. When we create

artworks, whatever subject they depict, as an artist, the ultimate wish is to

produce something that resonates with and connects the viewer to the work. It

doesn’t have to be vintage or retro inspired, it just needs to subconsciously

speak to the viewer.

The art needs to take them

somewhere, remind them of something, it needs to trigger an emotion and

hopefully provide the viewer with a connection either to the artwork or the

subject the art depicts, art is from this perspective, exactly what we are now

seeing amongst so many retro collectors, what they are collecting is often a

connection to the past and better times.

So alongside the need for

preservation, I always hope that someone can find some helpful nostalgic recall

and be reminded of the past to provide at least a glimmer of hope for the

future. Arguably, this should make the creation of art much simpler when

recreating memory invoking images of past times, but in my experience I’ve

found it anything but simple.

Whatever work you create has

to hit the sweet spot of believability, just enough to trigger a memory so that

the mind can then take over and apply its own set of filters. That’s when it

becomes a little more challenging, if you add into the mix some of the most

discerning and authenticity seeking collectors that I have ever come across, you

will find that many of these collectors will have an insatiable appetite for

authenticity, so recreating past times on canvas or screen isn’t quite as easy

as you would think.

|

| Eighties Rock Guitar by Mark Taylor – This is the guitar I really wanted back in the 1980s! |

With the 1980s pixel art style

becoming an increasingly-popular artistic trend, if not close to being seen in

the mainstream as a movement, the use of modern technologies to recreate

vintage graphics leaves those of us who lived through the 8-bit era a little

empty. Sure, the work is often a nod to the formative years for those of us of

a certain age, but for a real nostalgia hit I always find myself looking for

something well, a little more authentic than most of the recreated memories I

see hawked as being retro on marketplaces such as Amazon.

When I say that pixel art and

retro more generally is becoming a trend, the reality is that in some circles

pixel art and that vintage aesthetic have been an artistic staple for as long

as I can remember, it’s certainly nothing new.

Pixel art is now becoming more

popular in the media and certainly, the style is being increasingly used in

graphic design partly because the world loves nostalgia and it’s a great way for

a marketing team to build a connection, but looking back through the history of

digital art over the past four decades, I would say that pixel art has been a

legitimate artistic movement for a while, some of my own collectors have been with

me since the 80s.

So why is it suddenly so popular, I think mostly that it’s just that the press

didn’t cover it quite like they do today, and some consumer products from the

decade are beginning to turn up in auction houses and fetching eye-watering prices

for stuff we often think we still have somewhere in the attic before realising

we threw it away when we last had a clear out. 80s prices can be a media frenzy

of shock and awe.

Many of us original pixel

pushers have already made decades long careers out of creating this style of

art and many of the processes I use today are no different to the processes I

used back in the 1980s and 90s. Indeed, many of the commissions I get today are

commissions to do the same things I was doing in the 80s and 90s. To some, that

might sound as if my career has never moved on to doing something new, but that

couldn’t be further from the reality, there is always something new to do and

something new to learn about the three decades I cover.

Whether it’s the side art for

a video game cabinet or pixelated assets used in a retro-inspired video game,

or even recreating the ephemeral content that was packaged with 1980s products

and games, I can’t really think of anything that I do today that is all that

different to when I first started out, except I’m now doing more of it, with a

far greater appreciation and understanding, especially now there are an

increasing number of people looking to collect everything 80s and 90s.

|

| Geometric Emotion by Mark Taylor – an 80s colour pallet and he mainstream introduction of Polygons at the back end of the 80s and early 90s was the inspiration for this piece. |

If you are serious about

creating retro/vintage-inspired works, you really do have to convey a sense of believability

for the work to resonate with the viewer. I’ve been painting 80s life and have been

involved with 80s technology since the 80s and I have to say, creating vintage

style art with any level of authenticity with modern tools can be challenging

because the tools we have today are simply, too good. We didn’t have the

distraction of 8K BS, we had fuzzy and noise and overheating power supplies.

The equipment used to create

this type of art and graphic design in the 80s was minimalist compared to

todays technology, and by minimalist, that’s a massive understatement I think. This

creates a challenge for any artist who wants to create truly authentic looking

work with modern technology, it’s not even on the same level. Nowhere even

close.

So much of the pixel art that

is created today looks brilliant, it’s clean and crisp, usually very colourful,

and it mostly has a very distinct look and feel. But what it doesn’t have is

any authenticity at all. This is fine for many casual fans of the 80’s genre,

it nods back to a period in time, but if your collector base is built from

vintage, rather than retro collectors, (there’s a difference we’ll touch on

later), this modern approach and the look of modern day 8-bit graphics feels

too much like an abstraction and it can fail to connect those harder-core

vintage buyers who are looking for authenticity.

Just to clarify and recap very

quickly from one of my earlier retro articles, and I will paraphrase here for

brevity, retro is a modern interpretation or recreation of something of

vintage, though the terms are often used interchangeably. Collectors of retro

computer games for example are really collecting vintage games if they are the

originals, they would be collecting retro games if they were made more recently

to look or act like the originals. Generally, in the collector world,

everything comes under a retro heading just to confuse and bemuse!

There’s one thing I have had

to learn over the years and that is, to persuade buyers of retro and vintage

inspired works to choose one work over another, is that you have to add that

believable layer of authenticity to the work. What I’ve generally found is that

buyers are usually buying it to add to a collection of similar works from the

period they’re collecting, or they’re buying to provide a period specific

aesthetic alongside a retro or vintage collection.

Something else I have learned

is that dedicated vintage collectors are willing to pay more for authenticity

which is pretty awesome as an artist, but that does bring a level of complexity

that might make it more challenging for some artists to serve that particular

market.

Vintage, as opposed to retro

collectors are also a very vocal bunch when it comes to this ask for authenticity.

Ideally they would be buying genuine work from the period in time but that’s

not always possible. That might in some cases be down to the often

over-inflated expense of buying almost anything vintage, or down to scarcity.

That’s not to say that most

things from the 80s are in short supply these days, you can easily find almost

any technology from the era, but finding mint condition examples is difficult

and when you do find a good example, there are plenty of people willing to sell

so long as you also pay what has become known as the retro tax.

The media hype around retro

has made collecting anything vintage, trendy. What you will see as a collector

today is that there will be many people scouring their garages and attics to

dig out items from the 70s, 80s and 90s, and then they will promptly upload

photos of those items to eBay and describe them as super-rare. Honestly, there

is very little from any of those decades that is super-rare when it comes to

technology.

Those same people then apply

what we hardened collectors call the retro tax, a premium that doesn’t always

come out of demand and supply, but out of media reports telling everyone that

everything is more valuable than it is. There is then the media hype when

something seemingly once popular but is actually an especially rare example

such as a prototype or something that is factory sealed in original condition

sells for an eye-watering amount at auction. Made in the eighties isn’t a label

that also says it’s automatically rare or valuable.

Case in point, I continue to

use cathode ray tube TVs and monitors to create some of my retro and vintage

work on and I still use them whenever I exhibit my retro/vintage works as part

of my display. I can buy a good quality, working CRT TV for less than twenty

bucks quite easily, Facebook Marketplace is full of them, but as soon as the

seller calls it a retro CRT and maybe adds a line that suggests the TV is ideal

for use with old computers, the price can jump ten-fold, and there will be some

unwitting individuals who will buy into the hype.

If you are recreating vintage

work for collectors who are collecting an aesthetic trend rather than anything

more authentic, the modern-day abstraction/representation created with modern

equipment is usually going to be fine. If you want your work to appeal to a

much more niche collector base, and a collector base that will happily pay more

for that added authenticity, you need to be firstly become much more creative

in how you produce the work, and secondly, you often have to think beyond the

use of modern-day equipment to achieve results that the more niche collectors

will be happy to take over an original item.

I’ve had the same conversation

with many artists over the years about collectors of period specific work. From

experience, buyers of this work can usually be split into two very distinct

camps. The first camp is made from collectors who, like I said earlier, are

looking for the 8-bit retro aesthetic, it’s a trend, a nod to an age, it

provides a flavour of the past, and the second camp is looking for an exact and authentic look.

This is no different to

collectors of other art genres, there will be people who will be happy to own a

poster and others who only want the original work and a few who will be happy

with a compromise in between or at least a really good fake, not that I endorse

fakes, in my ephemera recreations I state on the images that it is a facsimile

of the original or a recreation, but mostly what these collectors are looking

for is an authentic recreation that provides the same kind of detail found in

the original.

|

| Old School Math by Mark Taylor – you might not immediately notice the level of detail in these pieces, below is a close up of the LED matrix on the screen. |

|

| All LED screens will have some level of visible matrix – it was very noticeable on 80s technology. |

The critical difference for

collectors who are interested in the 1980s is that the 1980s, and even the 70s

and 90s, were very disposable decades. Sure, you can buy almost any technology

from the time, as I said, none of it is really super-rare and it might have

been built at low cost at the time but it was usually built to last, hence I

still use 40-year old computers today. The ephemera on the other hand, the

boxes, the stuff that came packaged with the thing you are buying, most of that

stuff was thrown away.

Another case in point here, if

you take video games from the 80s as an example, most kids would take the game

cartridges out the box and throw the box and the instructions away. That’s

exactly why there is such a huge market for recreated boxes and packaging these

days. Last week I found an original box for an early home computer without its

contents on sale for £400 (UK), the computer that went inside was available for

£80 (UK) unboxed, and I have little doubt that someone made the purchase of the

box, now whether they will get the whole £480 back if they were to sell both

together is another story, collectors of vintage technology tend to hold on to

it rather than sell it.

A recreation of a Colecovision

video game cartridge box will probably set you back thirty bucks or more in

some cases and that’s without the game cartridge or any manual included, an

original empty box for the console, and one that’s in nowhere near pristine

condition can set you back at least a hundred bucks, if it’s pristine or a very

good recreation then you can expect to double or even triple the value

depending on your location.

As an American console, here

in the UK the Colecovision console box could fetch considerably more in mint

condition because the console wasn’t as popular over here, I did own one and

regret selling it on every day. A recreated console box with polystyrene

inserts can cost just as much as a console, often more, and these things sell.

This is the level of

authenticity that the more niche collectors will be looking for. Most artists

who recreate vintage packaging are now having to place customers on wait lists,

I’m even having to do this at the moment for some items of my recreated

ephemera, especially manuals where the wait list can be even longer if I need

to track original reference copies down.

If you are looking at art as a

means to provide you with a living wage, there is a living to be made from

nostalgia. I know a number of artists who make a healthy living creating the

aesthetic look and feel of the 80s using modern technologies, but if you are

prepared to put the work in and, at this point I have to say you do really have

to have a passion for the period, the real living to be made is in the more

niche market of vintage collectors who are looking for that certain level of added

authenticity and products that enhance the collectability of products they

already own.

This is the retro world’s

equivalent of the high-end fine art market, where a pristine and factory sealed

example of a mass produced and hugely popular video game (Super Mario) can set

you back upwards of a million bucks. Although, I’m not convinced that the

market for that game wasn’t well and truly played a little here. We’re now in a

time when video games can be graded and encapsulated in the same way we might

grade rare coins.

I would also probably add that

unless you have a real passion for the eighties, you might not ever find any

real level of traction with the high-end 80s collectors unless what you are

offering is above and beyond what’s already available. If you are simply

looking to create art that sells in volume, the retro aesthetic might be as

good as it gets, it’s still a tough and crowded market to enter but there are

plenty of buyers. If you are looking to engage with more serious collectors, it

becomes less about the money and more about the art and recreations that you

create and your knowledge and passion of the period they are collecting.

It’s also worth bearing in

mind that creating 80s vintage works isn’t just about recreating images from

video games or the technologies of the day. The eighties was responsible for

the Memphis Design movement which continues to be used in many retro-inspired

designs today, and I suspect in many cases, it is a style that is used without

any depth of knowledge about the movement itself.

That’s not to cast any

dispersion on the ability or skill of the artists creating it, it was a look

that defined the 80s as much as anything else and there is nothing that screams

1980s louder than the patterns used in the MTV logos used throughout that

period in time. But, it was a relatively short-lived style that is too often

only remembered for its visuals rather than its origins.

Today, it’s a design style

that is often used in the wrong way on the wrong products, but understanding

how and when Memphis Design styles were used can make your retro-inspired works

and recreations much more appealing to collectors of period works.

Memphis Design began with a

gathering of architects and industrial designers in Milan, Italy, in 1981. They

were dismayed at how creativity had stagnated and become corporate and uniform.

They looked back to the works of Kadinsky, the abstract shapes and colours of

cubism, De Stijl and Harlem renaissance art and the pop-art movement of the

1960s, and they then incorporated elements of popular low culture into a very

distinct style which was of liberation and joy, yet today it is often

associated with rebelliousness.

After the inception of the

style there was an exposition of these

gaudy, outlandish works and in a parody of high class culture it caused massive

disruption in the design community and even its haters found it difficult to

avoid this new artistic trend of neon pallets and swirly patterns. It was intentionally

created in bad taste to fit in with a decade that gave birth to glam metal and

shoulder pads, and was in sharp contrast to the austerity of the Reagan

administration in the USA.

The Memphis group closed its

doors in 1987 after Black Monday but its colourful style persisted well into

the 1990s where it gained even more traction after being integral to TV show

sets such as Saved by the Bell.

As an artist, there’s a fine

line in creating anything from the period with any authenticity and creating something

that just looks either dated or too modern. This is why as an artist it is

important to make sure that you do your homework and pay attention to the

detail.

Research is a very useful

skill to develop which will help enhance your historic knowledge of whatever

period your work depicts. Having that knowledge will make your creative process

much easier and your creative output will stand up better to what I like to

term as, collector scrutiny. The details as I’ve mentioned already really do matter

to high-end collectors, I can’t stress that enough.

|

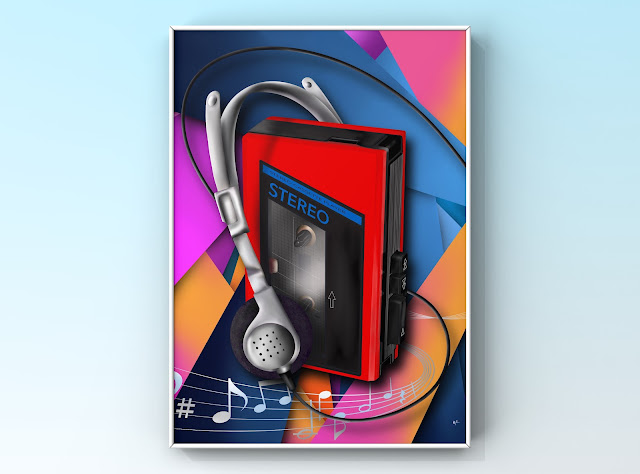

| Life in Stereo by Mark Taylor – Those headphones were great… at the time. Today, not so much but they are still popular on eBay! |

When I look at old technology

I distinctly remember its subtle nuances, but technology has changed

exponentially and many of these nuances have been lost through iterative innovation

over the years since. To a collector, it is those tiny details that can make a

wealth of difference in triggering memories and evoking any kind of emotion for

times past.

Pay attention to the detail as

an artist and this can negate the negative comments on social platforms and it

can be the difference between collectors selecting your vintage-inspired work

over someone else’s. Whilst there is a lot of great work already out there,

very little of it drills down into the level of period specific detail that high-end

collectors want.

If I could offer one piece of

advice to any artist looking to create retro-inspired works and vintage

recreations beyond creating retro-themed designs that have more of an aesthetic

rather than collectible function, that advice would be to get your head

completely in an eighties (or any other period specific) space.

For retro works that depict

the output from old technology, such as recreating those pixelated 8-bit images

that have become so popular, it’s worth understanding how much different the

technology in the 80s was compared to the technology we use today.

Understanding the nuances of 8-bit graphics compared to something you could

produce on a modern PC with Photoshop will help you to recreate some of that

authenticity that is often missing and with a little period knowledge, it’s not

especially any more difficult to create a more authentic piece of work.

I think to an extent, it’s

also worth understanding how the industry operated too. Many of the graphical

styles came about as a result of how the machines had been built. They were usually

to retail at a low price point, and partly, due to the businesses practices of

the day which focussed on pushing product out in the shortest possible time

frame. This often had an impact on the quality of the visuals meaning that more

often than not, you really don’t have to overthink some of this type of work. The

detail is often more about what’s missing rather than what’s there.

Magazines of the period are

interesting in that the screen shots they would print would usually be of

moving images that couldn’t be paused. What the magazine photographer would

need to do is to build a dark housing and use a traditional camera, capturing

multiple shots to hopefully capture the shot they are looking for.

In some magazines, they would

build contraptions where the camera could be operated with the foot as the photographer

played through the game, so anything published was usually published not as

clearly as you would expect from a magazine today, but with added noise, maybe

a few light trails, and certainly never at the resolution we might expect to

see in a magazine today.

My professional art story began in the early

eighties not too long after I received a home computer from my parents as a

Christmas gift. The year was 1980 and the home computer I was gifted one

Christmas morning arrived under the tree as a kit that needed to be built. Once

assembled, it connected to the TV and well, it didn’t do very much. If I had

been thinking that it would compete with my Atari VCS and allow me to play

video games and listen to the exciting beeps and well, beeps, I would be

mistaken.

There was no sound, there was

no colour, it displayed text, often not very well, it had way less oomph than

the Atari console which by then was woefully underpowered itself, (it was

purposely underpowered on its own release day) but the excitement came from

being able to do something other than move abstract pixelated representations

of stick figures around in a video game.

I was finally able to create these

abstract representations, well, sort of. I was able to place characters on a

screen and interact with them and as a naïve child, that seemed to me to be the

future. By now we were still only a few steps beyond the original Pong video game

that made history during the 70s, but it was the control given to the user that

took it to a new level.

Exactly a year later I found

an upgraded computer under the tree and this time it had been assembled in a

factory, it didn’t flicker on and off each time a key was touched, and I say

touched, this was touch well before we had touch screens.

The keyboard was a plastic

membrane with printed keys for the keyboard, just like the last one but with a

little more added oomph that had been missing a year earlier. It still had no

sound and it still only had two colours, either black or white but it had a

whole 1Kilobyte of memory. (Yes, 1024 of those kilobytes are needed for a megabyte,

which is still not enough to store a music track). Thinking back, I can’t even

contemplate how we even managed to fit so much in so little, an entire game

could run in less than 1 kilobyte, 16 or 48 kilobytes if you were lucky, you

had no choice other than to be efficient at coding and so often that efficiency

wouldn’t leave any room for overly complex images to be displayed. There would

be no work for digital artists in this arena for at least another couple of

years but that didn’t stop us from pushing the pixels around.

Not wanting to raise too many

expectations here but that added oomph still seemed to be less than the Atari VCS

which had been released in around 1976. The earliest home computers by around

1980 technically had more power, but they didn’t have cartridge based software

where the cartridges would often have additional components included that would

provide added functionality and more power to the console.

So whilst the early

microcomputers were technically more advanced they were also often less capable

and more limiting, rarely displaying their output in colour and they frequently

had no sound. But they did have a keyboard and a programmable language, and

that was all that was needed back then.

It was these limitations that

drove the initial creativity in the home computer industry and those very

limitations taught me and many others some very early lessons in efficiency

that would lead to forming the foundations that would later introduce me to a

wide range of programming languages, BASIC, Forth, Fortran, PASCAL, and 6502

and 6508 Assembly. Bear in mind that early digital art wasn’t created in

packages such as Photoshop, each pixel on screen was programmed in using

whatever code the computer understood. At first this would be something like

BASIC, later it would be assembly, today we just fire up Photoshop or we’ll

turn to AI.

Getting to grips with any of

these early and simple programming languages would be useful to understand the

languages in use today. When coding in HTML or C or any other modern day

programming language, having a grasp of those early languages has been

massively useful as it is those old languages that underpin pretty much every modern

programming language of today. If you are about to learn C or anything else,

grab an emulator and learn BASIC or Assembly, the modern language will be way

easier to get to grips with!

Maybe what’s more remarkable

is just how much you could do with 1kilobyte of memory. Today, modern coders

are nowhere near as efficient in their programming because they have the luxury

of almost exponential power. If more RAM is needed then it’s a simple upgrade

using relatively cheap components, back in the 80s, we would have no option

other than to become really creative in how we got the machines to carry out

instructions so that the need for additional and expensive RAM would be

negated. Contentiously, I’m going to go there, modern programmers have it

almost too good and that makes modern code generally pretty sloppy and

inefficient.

Today, my process frequently involves

setting limitations and working within them. Of course, it’s not always

possible to do, we have higher resolutions, different display technologies and

we don’t all have access to working vintage technology on which to create new

vintage works, neither would that be entirely practical for most artists to do.

But setting limitations around colour pallets, resolution, and even brush sizes

will bring you closer to achieving a more authentic look.

By 1982, things had changed

and technology was in comparison to at any time before, almost abundant in

supply, massively more inexpensive than ever, and the missing oomph had by now

been included. The game (literally) began to change in every conceivable way,

especially when it came to pushing pixels around the screen. The beeps had

matured to beeps that could vary in pitch and duration, and by the end of 1982,

we had powerful on-board sound chips that would sound almost orchestral.

Today there is an entire

demographic who buy chip tune music tracks, tunes created on an early computer,

mostly the Commodore 64 with its phenomenal SID chip and the Commodore Amiga.

The US really missed out on the Amiga through some bad business practices made

by Commodore at the time, yet it is a machine still used by many DJs and digital

artists even today, not least in part due to Andy Warhol’s mid-eighties works

created on the Amiga 1000.

This leap in technology wasn’t

the same story everywhere though. Small home microcomputers that were wallet,

and relatively user friendly might have been popular here in the UK where

almost every week a new model would come to market, but elsewhere and

especially in the US, Atari still dominated alongside Apple.

Despite new home micro’s being

introduced the same kind of buzz for microcomputers across the pond was

somewhat different to the buzz for home micro’s here in the UK.

Apple and a few others such as

Tandy’s Color Computer (CoCo) were steadily making inroads into the market. We

did get the CoCo here in the UK alongside the Dragon 32, a Welsh computer

broadly compatible with the CoCo, at least until Dragon was acquired by a

Spanish company. Apple with the original Apple and later the Apple II were

mainly focussed on the US markets.

The Apple II was a powerhouse in comparison to

most other machines, as was Commodore’s effort with the Commodore 64 a little

while later, and even its predecessor, the VIC-20 and Commodore PET, but then

the gloss fell away from a saturated US video game market and the industry

seemed to flounder for a while between 1983 and 1984. Business computers didn’t

have quite the same fate, but those marketed for the home became less popular

for a while.

Video games suddenly lost

their cool factor in the USA between 1983 and 1984, but we limped along quite

well in the UK and Europe, in part because the market was awash with affordable

home micro’s and there was a relatively strong academic program supporting the

use of computers in schools here in the UK. We also had an abundance of budget

video games available from the likes of Mastertronic, everything remained affordable.

When we talk about the great

video game crash of 1983, the crash was mostly confined to North America, we

certainly didn’t see it here in the UK or indeed in Europe more widely. It was

an especially vibrant time for the industry outside of the USA and much of the

retro-influence we see today isn’t always predicated on what would have been

popular in the USA, but elsewhere in Europe. Many of today’s retro aesthetic

works are very much of a European influence.

I’ll take a quick opportunity

to digress here, just as a point of reference, the UK and Europe influenced

much of what we see today in part due to video games such as Grand Theft Auto

and Tomb Raider being developed originally here in the UK. Even Nintendo would

use a British developer to produce historic classics such as Goldeneye on the

Nintendo 64.

A UK video game company, Rare,

was chosen by Nintendo to work on multiple titles and was based not too far

away from where I live today but they would be known before this as Ultimate

Play the Game. They were seen as a leader in developing titles for early

British home micro’s that are more and more in demand these days in the USA

where the vintage computer collector base is becoming massively focussed on

British home microcomputers of late.

Digressing over and back to

the 80s when Atari took most of the brunt for what is now known as the great

video game crash. More specifically, the crash is often wrongly attributed to

the poor job and oversupply Atari had done with the release of their ET game, a

game that became almost folkloric in that twice the number of game cartridges

were produced than the number of consoles owned. Added to that, Atari sent the

overstock to a desert landfill, although the real story is a little more

complicated than that.

Here’s the thing. It wasn’t ET

being labelled as the worst video game in history that paused the market in the

US, neither was it Atari, it was a combination of oversupply from dozens of

manufacturers joining the silicon gold rush alongside some ropey industry

management practices and sketchy quality control within the sector as a whole

and the emergence of many, many, new platforms, too many that would quickly

become unsupported or would bankrupt the manufacturers when coupled with all of

the other poor management decisions being made at the time.

The ET game had been developed

in five weeks so it was never going to be a triple A title, but hype and Steven

Spielberg together sold silicon. As a game, it wasn’t completely terrible and

it does retain some fans even today, but let’s be clear, Atari’s ET game was

made into a scapegoat that just so happened to take the focus away from the

real issues in the valley.

Today, the Atari ET game

cartridge can be picked up for small pocket change, the box on the other hand,

that’s a different story and again this has presented many modern-day artists

with a revenue stream in recreating the ephemera and packaging and much of the

retro work that is seen today is often based on the look of the graphics that

were made famous by Atari’s late 70s and early 80s games consoles.

That said, there was no

industry blueprint for anyone to follow in the 80s, least of all those at the

front who were introducing new technologies to the world. It was an era of

digital pioneers when no one really understood the market and the market was

struggling to truly understand the technology. People were literally making

things up as they went along.

Consoles would eventually revive

the US industry with Nintendo’s introduction of the N.E.S (Nintendo

Entertainment System). Every American friend I had at the time and have spoken

to since seemed to own the N.E.S, to the extent that I did ponder for a while

if it was part of some government program that gave them away.

But these consoles were not

user programmable computers which had remained popular in the UK and Europe. We

didn’t get sight of the N.E.S here in the UK until a while later which gave British

and European brands such as the likes of Commodore, Sinclair, Acorn, Oric, and

later, Amstrad, some room to breathe.

The US did get to see at least

a couple of these brands but in the case of Sinclair, it would have been known

in the States as Timex following a deal that had been done with the UK brand

owned by Sir Clive Sinclair. This didn’t change the fact that home micro’s were

nowhere near as prevalent in the States as they were in the UK and Europe

during that time and as a result, pixel art in the States was a little more

complex and somewhat less accessible and massively more unaffordable to create than

it was in the UK and Europe where affordability played a major role in selling

home computers and encouraging users to become creative.

|

| Three Point Five by Mark Taylor – another work featuring the 80s calculator – the detail here includes detail on the page, my signature appears in the text on the page! |

When I say that in the UK

things were vastly different in the home computer industry, that doesn’t mean

that things were necessarily always better. We struggled in the UK and Europe with

oversupply, poor quality, and bad business practices within the industry just

as much as anywhere else. Possibly more so as everyone was suddenly in the

business of supplying software that was often rushed and publishers desperate

for new IP would lap it up and pay for almost anything so long as you could

keep supplying them with code.

In truth, they would take

pretty much anything and place it on a store shelf safely in the knowledge that

someone would buy it. I know because even I created a game for one of the Atari

8-bit micro’s that never really went anywhere commercially, hey, I was about 14

when I wrote it. It wasn’t a great game even for the time on reflection, it was

rushed, it took me around a week in the evenings and it didn’t particularly

sell very well even though publishers never shared sales numbers with the

creators.

Yet the game I created, along

with a rudimentary image editor, a basic inventory tool which had originally

been created for my father’s business and another small game written entirely

in BASIC had all ironically sold a little better than the game written in a

much faster assembly language.

Some people were earning some

significant sums of money from generating some pretty rubbish code, others were

earning slightly less for better quality, but what I had produced at the time

still gave me enough to pay for a car in cash when I was 18 years old. Financially

the rest of the world was in turmoil but in the 8-bit world of microcomputers,

I’ve never seen anything like it before or since. If anything from the 80s

could magically happen again, I would have to say I would hope it would be the

8-bit gold rush because plenty of us were making bank for creating small 8-bit

images and coding very simple games!

What seemed to happen in the

UK and Europe was that a different direction had been taken than the one being

taken everywhere else. Very few of the home micro’s were being marketed as

games machines instead they would be targeted towards an education market, and

much of that was simply down to the government recognising that computer science

should become more established in early years schools. Yet those schools never

taught people how to create digital art, that was just a side-benefit that

happened out of necessity, games needed graphics, and programmers slowly

learned that they weren’t artists.

There seemed to be a different

view in the UK around how computers could be used for creativity. That’s not to

say that the value of the computer was not recognised elsewhere, MIT for

example gave birth to some of the most prolific coders of any generation before

or since. US developers were prolific in their support for the early Apple,

Atari and Commodore computers as well as the huge arcade industry born in the

USA.

Inadvertently, the arcade

industry helped to shape the creative industry by bringing art and technology

even closer together. That multi-million dollar industry that would be fed on

quarters spawned a whole generation of artists who would mostly remain

anonymous for many years. In the background they would work on graphics for the

arcade games in an ultra-competitive space, but they would also be instrumental

in designing the arcade cabinets and side art, most of which would be silk

screen printed.

Here in the UK, I was

beginning to establish myself as a creator of digital images, but for the most

part, artists were never really an absolute requirement in the home computer or

video games industry. Coders tended to create their own art, usually badly, and

it wouldn’t be until the 90s that digital artists would really begin to come to

the fore and at least occasionally get some kind of mention in the credits.

My entry to the art world has

been documented before so I won’t reexplore it fully here, but suffice to say

that during the 80s I had begun the transition from creating art on traditional

mediums to pushing pixels around on a screen, and with the innovation we

started to see in printing technologies, having the ability to sell prints of

that work meant that I was able to turn what was once a mere childhood hobby

into a fully fledged business.

Remember, this was the very

early eighties and even way before Warhol had touched the Commodore Amiga home

computer and recreated the Campbell’s Soup Can in a digital form. Yes, people

did create digital art before Warhol, he was simply way better than anyone else

at grabbing peoples attention.

It would be another three

years beyond 1982 and another couple of microcomputers before I took on my

first paid commission to produce digital art, a genre so new that we had really

only just started to call it digital art in a mainstream sense, although

earlier digital art goes back to the early 1960s and even a little before.

Neither did we call it pixel art as it is sometimes referred to as today.

Looking back, even though the

term digital art was being loosely used what we were doing with computers

wasn’t really recognised as artistic, certainly not in any meaningful way or

even close to being recognised in the same way that digital art is recognised today.

Very few people understood what digital art was and others would dismiss it as

non-art.

Only recently, and maybe even

in the past five or six years has digital art become more ingrained and

accepted as art in the mainstream and there are still those who continue to

hold out that digital works cannot be art. This might surprise many people but

despite digital art’s long history even before the birth of the 80s home

computer market which would make it more accessible to artists, it’s often seen

as something new that requires little to no skill to achieve, which couldn’t be

further from the truth.

Commercial digital art was by

and large, even in the mid to late 80s still very much a traditional and mostly

manual process of laying things out on paper. Image editors were still few and

far between and professional publishing applications were rare and expensive, and

they weren’t that great compared to todays applications, they would only really

be used in the high end media industries and the press until we started to see

releases such as Delux Paint on the Commodore Amiga.

|

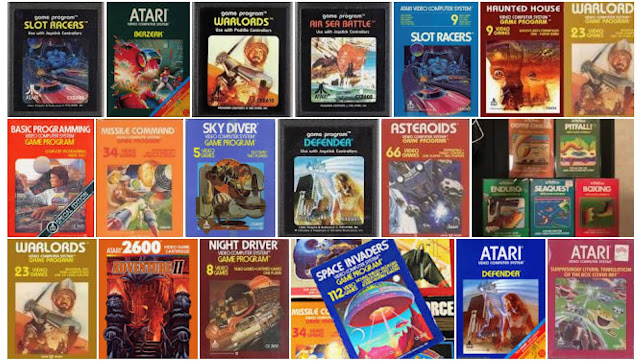

| Atari Box Art 1980s – Copyright Atari – These boxes are in demand today and recreations are available! Amazing artwork on every one! |

Before the digital art

application, if you needed an image to appear on screen, you mostly had to

learn how to program it either through early programming languages such as

BASIC or you would need to learn assembly language which was specific to each microprocessor.

Few programmers would take their work to the next level and design their own

image and sound editors but by the mid-80s, I had fallen in love with Delux

Paint on the Commodore Amiga, a machine that was completely misunderstood

outside of the UK and Europe, but one which now has thousands of users and fans

around the world.

Mostly, pre-Commodore Amiga, we

were dealing with 8×8 blocks of pixels and trying our very best to make that

small area pop with colour, mostly the same colour, and we were also trying to

be as photorealistic as possible which was impossible with the technology we

had, but like I always say, eighties kids had the best imaginations.

Nothing we could do with the

technology we had was even close to being photorealistic back then, all we had

were pixelated structures with jagged edges, it was a look that defined the

video games scene of the eighties and well into the nineties, but still a step

beyond the earlier consoles such as the Intellivision and Atari Video Computer

System, and with this new-found power, digital art was beginning to emerge in

its pixelated glory.

Chunky pixels were the only

option and would be until much later when we saw the introduction of 16-Bit

computers and later PCs, but it was never the intent of any of the original

pixel artists to be pixel artists, we were just creating pictures and artworks

with a purpose, the purpose usually being to convey a message to the viewer or to

provide a playfield or character whilst all of the time trying to make the

images not look like they had been created on a computer.

There was a graphical leap

forward in the 90s and this made things easier and graphically, closer to

photorealism. For a while developers had been stitching together four unique sprites

to create bigger animated characters and manufacturers had begun to turn to new

technologies such as graphic cards for the PC and alternative graphic modes

such as mode 7 on the Super Nintendo.

In most cases where cartridges

would be used, additional chips would be included – pushing the price of the

cartridges up in price, but by the end of the 90s consoles began to utilise CDs

which saw the introduction of 3D environments, probably way too early for most

developers who found it a real struggle with some of the hardware to produce

anything convincing in 3D, but that’s what the paymasters in the industry

thought the world wanted.

64-bit technologies would

become the game changer that 3D needed but the underpinning CD technology was

still considerably more expensive than the floppy disc or even the compact

audio cassette that had been used for much of the 8-bit, 16-bit and in the

early days of the 32-bit era.

In the 90s, 128-bit

technologies were being explored by some manufacturers but this would put the

technologies that took advantage of it out of reach for many and when higher

bitrate technology was introduced in the popular hand held devices of the time,

it would come at the cost of battery life making them less portable because you

needed to remain tethered to a power supply.

Graphically at the time,

128-bit wasn’t always as good as the earlier and lower bitrates for graphics. Developers

really struggled with the complexity of the systems and creating 128-bit

graphics would need even higher end development systems putting them out of

reach of most developers. As a graphic artist, I certainly couldn’t afford to

make the move to 128-bit systems on my own, so larger teams would be parachuted

into development houses and development costs became eye watering.

By this time we were beginning

to see advances in rudimentary graphic tablets that had been used before,

although for 8-bit artists, the TV screen would become the tablet for a while

as a light pen could be hooked up with the aid of an expansion card plugged

into the computer in most cases. Graphically, I never gelled with the light

pen, TVs were always upright meaning that they were just not conducive to

creating art. So what we did see at the time was that most programmers and by

now, a handful of dedicated digital artists who would continue to create art

using either a joystick or later in the 80s, a mouse. Still on 8-bit, 16-bit or

occasionally 32-bit systems.

The introduction of graphics

cards pushed the boundaries of creating digital art, but the downside was that

there were really no agreed standards. Game developers had a difficult time

optimising their code to work with the literally dozens of differing

technologies available, but we were by now beginning to see digital art that

was far beyond the limits placed on earlier work by the technology.

Today, retro art is a movement

but it’s not really vintage…

There’s some level of irony in

that modern digital artists strive to recreate that 8-bit, retro, vintage,

pixel style. In the eighties it was a style we couldn’t wait to move away from,

yet today I see so many artists painstakingly setting up grids in Photoshop or

Illustrator in an attempt to achieve the same kind of look that we once had no

choice other than to use.

The challenge we have today is

that the modern way of creating pixelated images in a retro/vintage style

doesn’t quite achieve any level of authenticity when directly compared to

vintage pixel art that runs natively on an original 8-bit or even 16-bit

microcomputer. To start with, there was little use of dithers that would allow any

kind of gradation of colour until a much later period in time.

In the eighties, any gradation

between colours firstly had to be done with a very small colour pallet, usually

either 8 or 16 colours and mostly if 16 colours were available it would really

only ever be an 8 colour pallet with dimming turned on or off to give the same

hue a brighter appearance. Now that’s

how you market the same thing twice.

|

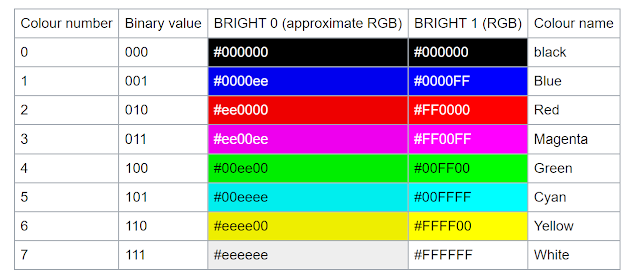

| ZX Spectrum Colour Pallet – that was all we had! |

For those unfamiliar with

dithering, in short, it means that an applied form of noise is introduced to

the image to approximate a colour that is not available from a mixture of the colours

that are available. By the time that the early home microcomputers of the 1980s

came out, dithering was already being used, it was even used during World War

II for bomb trajectories and navigation, and also in comic books and colour

printing which overcame the limited pallets available on earlier printing

presses.

Dithering really came into its

own on the early home micro’s but to create

any form of dithering was often a manual process as opposed to using an

algorithm to apply noise as we would do today.

Today, dithering is an

essential tool in the creation of many digital works, it’s also used in many

printer models to reduce the cost of printing. The inkjets spray microscopic

dots on the paper or print surface and even monochrome printers use the

technique to overcome the limitations of using only black ink. Dithering is

also the reason why you can still make out the detail of a colour photograph

when printing in monochrome.

Dithering is also massively

useful on the web even though most of us will have vastly more bandwidth today

than at any time in the past, the technique means that fewer pixels are needed

to build up the image so there is a reduction in the bandwidth used which means

that images can load much faster from a much smaller file size.

Even if you are taking

advantage of modern tools, what makes a lot of modern pixel art look too modern

to be totally convincing is in the simple things such as restricting the colour

palette. On vintage 8-bit computers and even early consoles, pallets were

limited as I intimated earlier, and it also depended on whether those pallets

were being displayed in a PAL or NTSC format so whatever format was in your

region would determine the output and the colour that you would see.

|

| Monochrome Pallet ZX Spectrum – Also demonstrate how dithering would work. |

Bright and dim colours on a

machine such as the Sinclair ZX Spectrum (Timex in the USA) and other micro’s

with limited palettes would be achieved by altering the voltage input of the

video display. On an NTSC video output you would also find that some machines

would display black only as a dark grey. Another factor that would change how

colours were output would be the actual display screen the image was being

output on, and the method with which the display screen was connected.

Output display resolutions and

technologies were vastly different too. There is simply no way that an original

eight by eight pixel character would have any impact today on modern 4K or even

8K displays, each pixel would be far too tiny to see and it would look like a

speck of dust on the display, it’s even problematic on a 1080p HD display or

even the lower HD resolution of 720p.

Today, images have to be

upscaled or stretched to fill a high resolution screen and mostly, they look

pretty horrible unless the effect of a single pixel is recreated with multiple

pixels and scaling up is quite challenging. Increasing the resolution would,

and still does to an extent, produce pixelation that would make the image look

terrible. Today, upscaling is possible and there are all sorts of algorithms

and techniques that can reduce the pixelation, but in truth, it’s still there.

You are seeing a reproduced copy of the original image even using hardware

upscaler’s.

|

| ZX Spectrum Colour Pallet Hex Codes |

Mostly during the 1980s we

would rely on graph paper and manually plot out the pixels that would appear in

whatever resolution the output would be displayed, in the case of the Sinclair

ZX Spectrum, the entire display was just 256 by 192 pixels and this was the sum

total of screen real estate that you had to play your game, view your art, or

type in a program listing.

Another issue with vintage

computers was that there could be what was called colour clash. Mostly, you

could only utilise a single colour in any character block so if the block of

colour moved over another colour, the colour of the block would appear over the

background colour. It was also known as attribute clash or more commonly today

we would think of it as colour bleed. 8×8 pixel blocks could only ever appears

as a single colour.

|

| ZX Spectrum Dithering 8 bit pallet – created manually often with code! |

This did provide for a unique

look and feel to anything appearing on screen and where modern takes on 8-bit

pixel art are clean, often with each pixel defined with its own colour, vintage

8-bit microcomputers, even the best of them could never achieve that kind of sharp,

clean, look.

The question for pixel artists

today is whether they go for a completely authentic look by limiting the colour

palette and include the effect of attribute clash, or whether they should

create a clean, modern representation. The choice is really down to the

audience, hardcore collectors are looking for that kind of raw detail,

collectors of fan art or an aesthetic nod to vintage, probably not so much.

The old displays that were

historically used generated a technically compliant NTSC or PAL signal.

Depending on your geographic region you would either see 480i or 576i

resolutions but the images would only be sent to one field rather than

alternate between two fields. This created a 240 or 288 line progressive

signal, which in theory could be decoded on any receiver that could decode

normal interlaced signals. If that sounds technical, I’m not sure any of us

original pixel pushers understood it either back in the day.

We would see horrible

horizontal lines on the display. Today these scan lines are seen as being a

charming and nostalgia inducing necessity in the reproduction of authentic

pixel art so it’s more likely today that you might utilise a transparent PNG

image of horizontal lines to place in front of the image when you are creating

vintage inspired artworks.

The scan lines were a result

of the shadow mask and beam width of regular cathode ray tube televisions and

monitors having been designed to display interlaced signals so the image would

appear to have alternative light and dark lines.

|

| RF Modulator – Now We Can Play by Mark Taylor – We did HD fuzzy. Originally created as a commission for a long-time collector, this RF modulator was the thing to have in the 80s. |

When you need to create more

authentic looking pixel images, you have a choice of either creating a modern

representation using modern tools or you go completely down the vintage rabbit

hole and begin to use ither original equipment or even emulation. No modern

tools can even come close to matching the visual limitations of 80s and even

90s technology, it’s simply too good, no matter how skilled you are. It’s not

really about having a high level of competency with modern skills or tools,

everything is already stacked against you when you are attempting to recreate

any level of genuine authenticity.

Any technology today is

designed to look clean, sharp, and be reproduced in a large format, often that

means 4K and above and a modern display just cannot get even close to

reproducing the phosphorous glow of an old CRT TV or monitor. At best, you can

hope for a facsimile of authentic pixel art but it will never be quite the

same. I actually feel a pang of sadness when I see vintage art displayed in art

exhibitions on modern displays, it’s not anywhere close to original without all

of the original limitations, not forgetting the phosphorous glow of a CRT or

the scanlines.

To counter this with my own

work, I tend to use a heap of layers, using gaussian blur tools over luminous

brushes in between layers before applying a scan line filter I created which

took me somewhere in the region of three months to produce. The filter template

I created has a slight curvature in the lines and every time it is used, I

alpha lock the layer and then apply a blend to provide the darker shadows

towards the edge of the screen before once again applying a luminous brush

stroke or three and using gaussian blur again to provide further reflection on

any layers above and below the scanlines.

You’ll notice this if you look

at any of my works that feature a screen, so long as you are looking close

up. I have licensed that template for

commercial use by other artists in the past, alongside a CRT colour pallet that

works in either Photoshop or Procreate, so again, there are so many potential

entrance gates for artists to offer buyers in the retro scene. You can see the level of detail in the LED Matrix on the calculator above. CRTs have similar levels of detail!

When there is a need for me to

tackle 8-bit art and even 16-bit art, there are some techniques that I always

fall back to because I know they will help me to achieve a more authentic feel.

Modern displays also have a

very different aspect ratio making it even more challenging to recreate

authentic images that would have originally been presented in a 4:3 format. The

technologies are vastly different which makes it a challenge to make a modern

display look like it’s an old display and this is why scanline filters are

often used to give images a vintage feel.

Transparent PNG images of

scanlines can be created relatively easily if you have enough time and with

tools such as Illustrator or even Photoshop, but these can still give an

entirely flat effect to the underlying image. Many of the freely or even

commercially available scanline filters never quite achieve a true

representation of the original look of a CRT, simply because CRTs had that

curvature and scanlines if they have no curvature applied will always look

flat.

I think to an extent, any

artist who wants to tackle vintage-inspired work and who wants to maintain an

authentic feel in the modern day with modern tools, will have it way harder

than we dinosaurs had it back in the day. We didn’t know that the future would

be 4K, hey, we were pretty amazed at what we already had. I also think that any

artist wanting to produce this style of art needs to work within some very

constrained limitations.

A lot of the work I currently create

doesn’t need to have any specific effects applied to it because most of the

time I’m reproducing memories of the eighties as opposed to a replica of pixel

image that would have been presented on screen. Having said that, there are

plenty of nods to old technology and in some of my works you will find individual

assets within the artwork that have been created on vintage computers, and

whenever I paint a screen, you will always see scanlines or the matrix used

within an LED display. Most casual users never notice this detail but for me,

it’s critical and for collectors who want authenticity, they expect nothing

less.

For me and my work, scanlines

are really as complicated as it gets for representational vintage inspired

work, but if I am working on individual assets that absolutely need to look

authentic, say for a retro-inspired video game that needs to retain an old look,

my process can be very different depending on what the commissioner needs.

Surprisingly, the easiest

commissions I tend to get these days are to develop images for homebrew indie

games that continue to be released on 40-year old microcomputers such as the

Commodore 64. They’re easy because I literally power up my Commodore 64 and

create the images on that just as I would have done some 40-years ago either

using a rudimentary image editor or I will program it in BASIC or Assembly

language.

|

| New Formats by Mark Taylor – the specification for the disc camera was better on paper. They looked really cool, the photographs were very poor compared to earlier formats. |

It becomes significantly more

complicated when you have to recreate old looks on new technology, I can spend

maybe as much as three or four times longer working in Photoshop than I spend

on creating the assets on vintage tech and that’s even after I go through the

process of bringing the final image over to new technologies for use as assets

or within an artwork.

Whenever I am create authentic

looking vintage-inspired that will be displayed and generated on modern

equipment or on canvas, I tend to apply

some very strict limits to the colour pallet being used. I also reduce the

resolution as far as I can to make sure that I can work with at least some of

the limitations from the past. For me, that’s kind of important because it’s

the limitation that drives my creativity, and for the most part I try to avoid

using Photoshop or Illustrator and instead use some fairly basic tools and

dedicated pixel editors for this kind of work, and where I can, I will use

original technologies or even emulation.

One of the more complex

effects I have to constantly reproduce is dithering. Sure, there are plenty of

tools that can dither the image automatically or reduce the colour depth and so

on, but if I have a commission that needs to be out of the door anytime soon

and I need the believability of authentic vintage images, I switch off

Photoshop and its multitude of distractions and fire up an old computer.

For all of the beauty that my

8K behemoth of a display foists upon my often weary eyes, I have to say that it